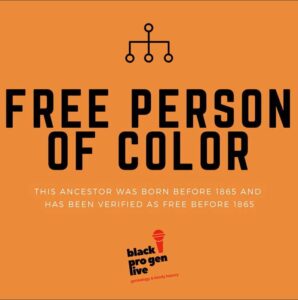

Free Persons of Color (FPOC)

Free Persons of Color (FPOC)

In America, there were individuals of African or mixed African and European descent who were legally free before the abolition of slavery in 1865. Their status varied significantly depending on geography, time period, and local laws, but they generally lived in a complex social space, navigating between enslavement and full citizenship. Free Persons of Color in America lived in a complex and often precarious social space. While legally free, they navigated a society shaped by racial hierarchy and oppression. Despite this, they contributed significantly to the development of African American culture, built communities, and were pivotal in the fight for civil rights and the abolition of slavery. Here’s a detailed explanation of who they were, their history, and their experiences in America:

FPOC

- Manumission: One of the most common ways enslaved individuals gained their freedom was through manumission, the legal act by which a slave owner freed an enslaved person. Manumission could occur for a variety of reasons: some enslaved people were freed as a reward for loyalty or good service, while others purchased their own freedom by saving money. Manumission rates varied by region and were more common in the upper South, urban areas, and under Spanish or French colonial rule.

- Children of Free Women: Under the legal principle of partus sequitur ventrem, adopted in the early 1600s in English colonies, the status of a child followed that of the mother. Therefore, children born to free women, even if the father was enslaved, would inherit their mother’s free status.

- Mixed-Race Heritage: Many free persons of color were of mixed race, often born of relationships—whether consensual or coercive—between enslaved women and white men. Some white fathers manumitted their mixed-race children, while others provided for them through education or property.

- Colonial Spanish and French Practices: In regions that were once under Spanish or French rule (such as Louisiana, Florida, and parts of the Southwest), a more flexible attitude toward race and slavery existed. These colonial powers allowed for a sizable population of free people of color, often descended from enslaved individuals or soldiers and settlers of African descent. Spanish and French laws permitted a more formal process of manumission and offered certain legal protections to free people of African descent.

- Legal Freedoms: Free persons of color held certain legal rights that enslaved people did not. They could own property, marry legally, testify in court, and sometimes vote, depending on local laws. However, their freedoms were always tenuous and subject to change, particularly as racial tensions increased in the lead-up to the Civil War.

- Restricted Rights: Despite their legal status, FPOC often faced severe restrictions, especially in Southern states:

- Voting: In many states, free persons of color were prohibited from voting, particularly in the South after the early 1800s, when states began to tighten restrictions on the rights of African Americans in response to fears of slave uprisings.

- Movement and Employment: Free people of color often had to carry freedom papers and faced curfews and restrictions on where they could live and work. Some states required free people of color to have a white legal guardian.

- Property Rights: Although they could own property, laws increasingly limited their ability to buy land or participate in the economy, particularly in the South.

- Vulnerability to Re-Enslavement: In some cases, free persons of color faced the threat of being kidnapped and sold back into slavery. This was particularly true in border states and places where the legal distinction between free and enslaved could be manipulated or overlooked.

- Geographic Concentration: Free persons of color lived throughout the United States, but their largest populations were concentrated in certain regions:

- Northern States: In Northern states, where slavery was either abolished or being phased out by the early 19th century, free persons of color were able to build communities, own property, and establish institutions such as churches, schools, and businesses. Northern states like Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York had significant free black populations.

- Upper South: States like Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina also had sizable free black populations. These states had a history of manumission, and many free persons of color there were landowners, artisans, or worked in skilled trades.

- Louisiana and New Orleans: In Louisiana, especially in New Orleans, a unique community of free people of color, known as gens de couleur libres, thrived. Many were of French or Spanish descent and were part of an educated and economically successful class of artisans, tradespeople, and landowners. New Orleans had a particularly vibrant free black community, with its own cultural and social institutions.

- Urban vs. Rural: Free persons of color were more likely to live in urban areas than rural regions. Cities offered more opportunities for employment, trade, and access to education, although even in cities, free blacks were often segregated and faced significant prejudice.

- Skilled Labor and Trades: Many free persons of color worked as skilled laborers or artisans. They were carpenters, blacksmiths, masons, tailors, and barbers. Some became successful entrepreneurs and landowners. For example, in New Orleans, free blacks owned businesses, ran schools, and even served in the militia.

- Land Ownership: While free blacks in the South faced increasing restrictions on land ownership, in some regions, particularly in the North and Upper South, they were able to accumulate significant wealth. In places like Maryland, free blacks owned farms and plantations and sometimes even owned enslaved people, often as a means to protect family members from being sold.

- Education: Free persons of color prioritized education, establishing schools for black children in the North and, where possible, in the South. Some free blacks were able to attend private academies or even colleges, though opportunities were limited.

- Community and Institutions: Free black communities built their own institutions, including churches (especially African Methodist Episcopal churches), schools, mutual aid societies, and fraternal organizations. These institutions played a key role in advocating for the rights of African Americans, providing support for the poor, and serving as centers of social and political activity.

- Racial Prejudice: Despite being legally free, FPOC faced significant racial prejudice and discrimination. In both the North and South, they were often viewed with suspicion by white society and were seen as a threat to the racial order. In the South, free blacks were sometimes perceived as a dangerous example for enslaved people, while in the North, they faced segregation and exclusion from many aspects of public life.

- Tensions with Enslaved People: Free persons of color often faced complex relationships with the enslaved population. Some free blacks, especially those who had family members still in bondage, were deeply sympathetic to the enslaved and actively involved in abolitionist efforts. Others, however, owned slaves themselves, either for economic reasons or to protect family members from being sold into harsher conditions.

- Restrictions and Laws: As the 19th century progressed, Southern states passed more laws restricting the rights of free persons of color. These included restrictions on movement, assembly, and employment. Some states even passed laws requiring free blacks to leave the state altogether.

- Racial Prejudice: Despite being legally free, FPOC faced significant racial prejudice and discrimination. In both the North and South, they were often viewed with suspicion by white society and were seen as a threat to the racial order. In the South, free blacks were sometimes perceived as a dangerous example for enslaved people, while in the North, they faced segregation and exclusion from many aspects of public life.

- Tensions with Enslaved People: Free persons of color often faced complex relationships with the enslaved population. Some free blacks, especially those who had family members still in bondage, were deeply sympathetic to the enslaved and actively involved in abolitionist efforts. Others, however, owned slaves themselves, either for economic reasons or to protect family members from being sold into harsher conditions.

- Restrictions and Laws: As the 19th century progressed, Southern states passed more laws restricting the rights of free persons of color. These included restrictions on movement, assembly, and employment. Some states even passed laws requiring free blacks to leave the state altogether.

Contributions to Abolition and Civil Rights

- Participation in the Civil War: Many free persons of color supported the Union during the Civil War, enlisting in the U.S. Colored Troops or serving in other capacities. Their contributions to the war effort were a major step toward gaining greater recognition of their rights.

- Post-Emancipation: After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in 1865, free persons of color found themselves in a new social order. The distinction between free blacks and formerly enslaved individuals largely disappeared as African Americans as a whole faced the challenges of Reconstruction, segregation, and discrimination. However, their earlier experiences of navigating freedom in a slaveholding society provided important lessons in community-building, resilience, and activism.